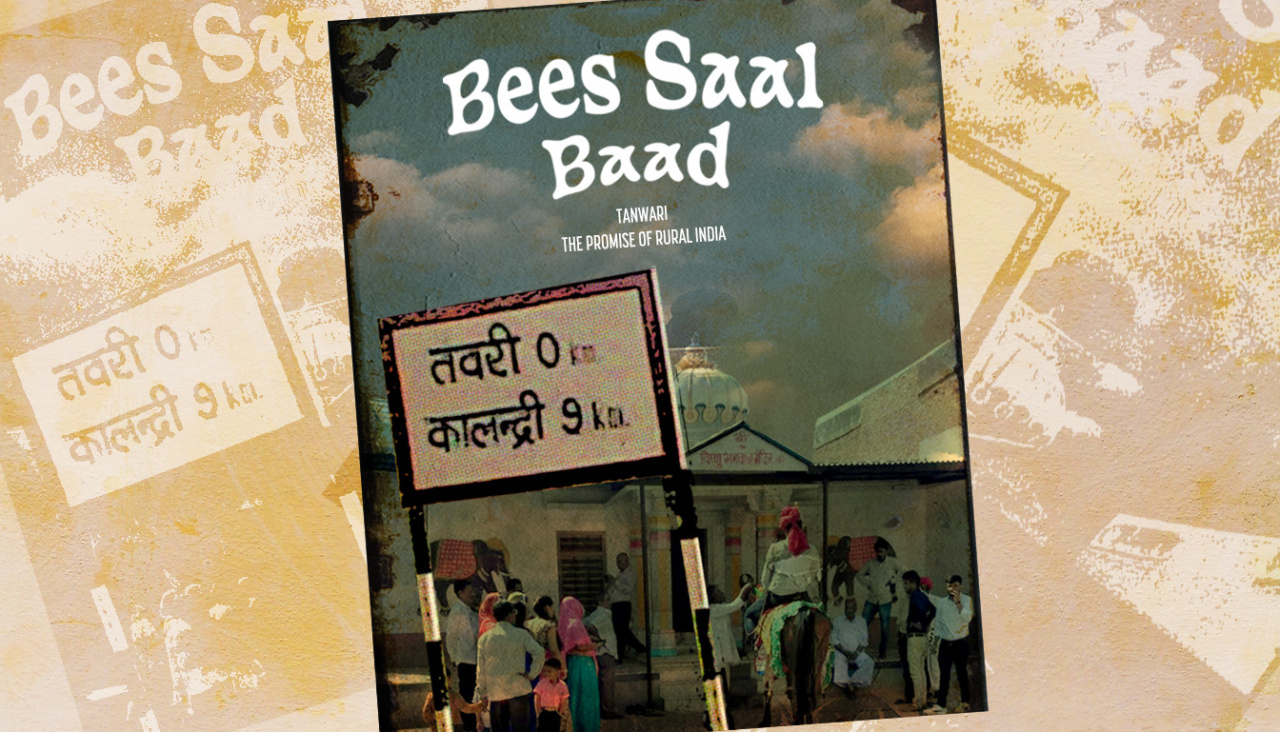

The title’s namesake film is a thriller that covers events in a village spanning 20 years. This writeup also covers events in my village, Tanwari in Rajasthan, spanning more than 20 years. Although this story is not one of suspense, it is nevertheless a thrilling one for anyone interested in the promise of rural India.

A long time ago, my father migrated from Tanwari in search of a better livelihood. We are a family of priests, and our vocation was doing puja (religious rituals) in the village temple in exchange for grains. However, there is only so much grain that one temple and one small village can spare to sustain an expanding and large family, so my father came to Bangalore in search of income opportunities. My mother and us kids joined him soon after, while our grandparents, uncle and the extended family stayed back.

I would go to Tanwari as a child for summer vacations. Even till 20 years ago, there was no (or very little) cash in the system. Everything was barter based, like my family’s puja services for grains. When my father’s brother was sarpanch (head of the village) in his younger days, he brought in a government school and a government hospital – that’s all there was in terms of facilities. And at best there may have been one shop – with no money in the system, what use were shops? In fact, till about a few years ago, Tanwari was not even on Google maps – the nearest landmark on the map was Kalandri, another slightly larger village about 10 kms away.

When I visited recently, my son went with me for the first time. This made me reflect on the changes in the village over the years – as I compared the Tanwari of old to the Tanwari of now, the shifts seemed quite dramatic. It made me wonder whether macro reports or data can ever be trusted to tell the real story of what is happening on the ground in rural India. So I have made an attempt to capture my experiences here, through different facets:

On the map

Today, Tanwari is up on Google maps and has a small Wikipedia page, thanks to local people becoming tech friendly. If one uses Google to track Tanwari’s satellite image, one will see that over a decade ago, Tanwari was mostly brownish – all sand. Now it has some small pockets of water and greenery. I will delve into the why of this later in the article.

Busy-ness

When I used to go for vacations as a kid, people would camp out at our place for the full day – they would gossip, have tea, eat, sleep, do nothing. There was little else to do in the village. This time when we went, no one came to visit except on the day we were leaving. Why? Because everyone is busy and has a job. This indicates how much economic activity has picked up. In fact, folks are now so busy that they don’t even attend functions. This was unheard of earlier – there were very few functions, and no one skipped the few that happened. Now there are more functions – again due to increased economic activity – and people don’t find it a big deal to skip a few.

Eventful lives

Continuing with the above point, events used to be major sources of economic activity in rural India. People would migrate to the cities but would do weddings and functions in their villages. So the rural economy got built around events and functions. Post Covid, all this got impacted and for two years there was nothing. Now people seem to be making up for the hiatus. In the 15 days that we were there, I don’t recollect a single day that did not have an event going on somewhere in Tanwari or in the nearby villages.

Schools and buses

From a single government school, Tanwari now has multiple schools to which the neighboring small villages also send their kids – one of the private schools even provides bus services.

Barbers, tailors and hawkers

Migrants sending money back home and visiting their villages for events etc. has fueled an ecosystem of economic activities. From hardly any shops 20 years ago, Tanwari has multiple new shops today – a barber shop, a sweet shop, mobile phone shops, tailor shops, stationery shops, vehicle repair shops, pharmacies and more. Hawkers selling food items like pani puri and falooda show up daily and have a throng of customers – this was unheard of 20 years ago. At best maybe we had a candywalla visit once a week or so.

Today there is a small factory in Tanwari that employs half a dozen people. It makes coriander powder, chili powder, pickles, snacks like khakhra etc. They sell it locally (earlier every household would prepare these items on their own and never bought them), as well as to tourists.

DJs and Flower showers

It is clear that discretionary spending has markedly gone up. To the point that there is a photo studio and a couple of ‘DJ’ shops that provide music services for weddings and other events. One DJ shop has been set up by a childhood friend’s son – they do drone photography and drone flower showers at functions! There are lodging and wedding resorts in some of the larger nearby villages as well.

Petrol bunk queues

Continuing with the above point, queues at the petrol bunk in Tanwari tell their own story of increased prosperity leading to ownership of two and four wheelers, even when the fuel prices are at such high levels.

The thriving real estate agent

Demand for land is going up, with migrants in the cities wanting to buy land back at home. Real estate assets are moving from near zero / negative rentals to rent yielding assets today. Earlier, we were paying the school master to live in our place so that it was properly maintained. Today we are getting rent for our property.

Showrooms are coming up for automobiles, banks etc. So are hotels / resorts, as mentioned earlier. Land rates on the outskirts of the nearest small city match those on the outskirts of large cities. Due to the demand, quite a few agricultural lands are converting to commercial / residential properties. Because of these developments, being a real estate agent has become a viable business. The agent in our area has such a flourishing business that he has become an investor himself.

Pockets of green

Agriculture cultivation is at its peak, given the subsidies, subventions for irrigation, and availability of capital to supplement the subsidies. This explains the pockets of water and greenery that now show up on the satellite image of google maps.

Salaried priests

My father had to migrate with his family as there was limited income opportunity for a family of priests then. But today, the branch of my extended family which stayed back in the village are priests of multiple temples in our village and around. What’s more, today priests are hired with proper salaries. Their income levels allow for a comfortable subsistence and they don’t have to think of moving out, like my father had to.

Sweet water

I remember as a child – the water in my village used to be very salty. I used to struggle to drink it. What’s more, we had to fetch it from a kilometer or two away. My mom’s village was 5 km away from my father’s – the water was slightly better there so I often used to stay in her village, even though it was a very small one with hardly 20 families. Today, everyone gets in a tanker with pure, sweet water for their households. They even get drinking water cans supplied to their homes. Prosperity and improved road connectivity have helped.

The optimistic taxi driver

The prosperity shows in the optimism of the people. I was chatting with Manaram, a taxi driver who drove us around on this visit. I asked if he would like to add a vehicle to his fleet and he was willing to take up a couple, he was so confident of demand.

Jam packed trains

Trains are running jam packed even in the AC compartments, with many people getting on at the last moment without a reserved ticket – another sign of movement and connectivity.

No place like home

40 years ago when my father moved from the village, people were ok with migrating to faraway places like Bangalore for a job – they had no plans of going back frequently. Today the few people who still migrate go to nearby locations, preferably an overnight journey away. They want to maintain a presence back at home, due to the opportunity available.

One can dismiss this story saying it is anecdotal. But our field visits to villages in Orissa, Karnataka and so on mirror the same reality. There are multiple triggers for this – a generation migrates to the city and brings back money – that is the first trigger. The money coming in is invested into some venture, say, a shop. This gets money moving through a series of transactions in the system. The second trigger for this is road connectivity, that enables transactions with the outside world. The third trigger is mobile and internet connectivity – people are now exposed to the same things that people in the cities are exposed to, in real time. They can see first hand what lives people are leading elsewhere. Aspirations to get to those levels are very high and people are willing to work hard to afford those aspirations.

Certain factors make this opportunity very unique. First of all, the informal sector does not keep money in the bank – their money is always in the market, so it is always at work. This leads to more economic activity and growth. Households are getting more prosperous as different members of the household pick up different income streams – managing a farm, running a shop, doing a job etc. A healthy life, greener environment and lack of pollution add on another layer of differentiation. In Bangalore, I always have a bit of a cough and cold. But in my fortnight’s stay in Tanwari, I had absolutely no health problems. People in the village breathe fresh air and eat better, fresher food. All in all, they have better health and immunity and are a far better bet as target consumers.

No macro data or survey will ever be able to capture this fascinating story. Is this an inflection point of economic activity in rural India? I certainly think so. The question is, is the rest of the world ready to acknowledge and tap into this effectively? Let’s keep watching this space.

I will end here with this video of Tanwari, taken by the drone photographer in our village:

P.S: Thanks Richa Pandey for all the help with this write-up